Chapter Six

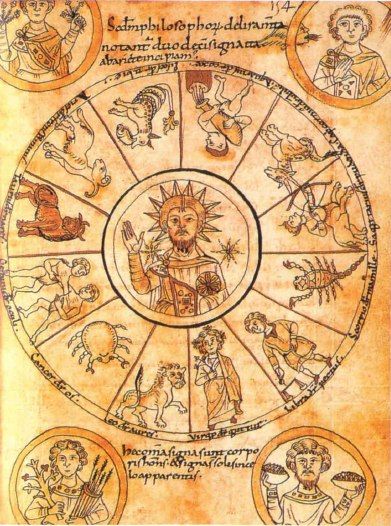

At the core of Christianity is a mystery. The Gnostic Christians embraced the mystery, while the Imperial Orthodoxy sought to minimize, control and literalize it. But the mystery persisted and not even the church councils of the fourth century could completely banish or obscure it.

Our modern view of the end of the world is entangled with the magickal mystery at the heart of Christianity. To understand this mystery and its alchemical and apocalyptic importance, we must first look at how the Hebrew culture of Palestine in the first century came to develop its unique perspective on the end of all things.

The existence of The Old Testament is not, by itself, remarkable. Many other ancient sources are just as obsessed with the end of the world. Flood narratives, such as that of Noah in Genesis, are common to almost every traditional culture on the planet. The Noah story originally comes from a Mesopotamian tale woven into the Epic of Gilgamesh. But the Old Testament is unique. Instead of treating its story as a chronicle or a collection of myths, The Old Testament was put together as a way to demonstrate the supernatural intervention of God in the course of human affairs.

The early books of the Old Testament display a kind of historical unity, as if they were intended to make sense together, even if they were written at different times and under different circumstances. Thus the passage of time is given meaning by its fulfillment of God’s purpose. This sense of historical spirituality made the Hebrew world view, and the Christian which grew from it, highly susceptible to the idea of an end to all things.

However, this sense of unity was itself the product of an apocalyptic event, the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians in 587 BCE and the subsequent return of the exiles a generation later. The Book of the Law of Moses, which Ezra read to the assembled Israelites at the dedication of the re-built Temple in 445 BCE, was a combination of ancient texts found in the ruins of the Temple and Mesopotamian myths absorbed during the exile. This new version emphasized the power of the Hebrew’s God to punish or reward His people. The historical nature of God’s effect was not lost on the survivors of the exile who heard this version of the Book of the Law.

In addition to a new sense of God’s involvement with the workings of history, the exile added another element to the emerging religion of Judaism. Where before the exile, the Hebrew prophets had been mainly concerned with the social issues of Israel and its relationship to God’s plan for it, after the return the focus shifted to an even greater apocalypse, one of cosmic proportions.

The Old Testament prophets, from the Greek word for ecstatic utterance, appeared around 1000 BCE as a type of monotheistic shaman. The “nevi’im,” or God-speakers, were considered, along with the priests and the sages, to be crucial for the spiritual health of the Hebrew people. There were great numbers of these prophets who performed frenzied rituals of dancing and chanting for large and enthusiastic crowds, which, not unlike the rituals that accompanied the State Oracle of Tibet, ended with a prophetic announcement. Taking their cue from Adam and Eve’s banishment from the Garden and the Flood, the prophets soon began to focus on the sinful nature of Israel and God’s approaching Day of Wrath.

Amos started the trend around 760 BCE, which continued in increasing urgency until the prophecies came true. Jeremiah, the prophet of the Babylonian conquest, was the first to connect the fate of Israel with the ultimate destiny of the cosmos. He predicted that “the heavens will shudder” with pure horror at God’s punishment. For those who experienced the Babylonian conquest, it certainly felt like the end of the world. What had been the essentials of God’s favor, a homeland, a temple and the right of Kingship, had all been taken away and destroyed.

Ezekiel, who was a priest of the temple at the time of the conquest, marks the beginning of the new apocalyptic prophets. Like Jeremiah, he predicted the end of the Israelite nation and the destruction of the temple. Ezekiel however used an amazing variety of symbols — fiery wheels, dry bones, chariots and multi-headed angels of marvelous countenance — to create a surreal image of transformative and apocalyptic processes. He brings together almost all of the elements used by future prophets to describe the End of the World, and adds a few new ones: a king from the house of David who will rule all mankind, the idea of a purified elect who will survive and, most important of all, the re-building of the great Temple at Jerusalem as God intended it to be. This image of a physical New Jerusalem laid the foundations for the Temple imagery in the Book of Revelation and contributed to the gnostic idea of chilaism.

But it was the Second Isaiah, a contemporary in exile of Ezekiel’s, who created the image of the apocalyptic messiah. The messiah will come, as Ezekiel said, from the House of David and be scourged and rejected. His message will be taken up more by the Gentiles than Jews, but in the end the Jews will be proclaimed as God’s chosen ones. A new covenant will be declared and a new heaven and a new earth will be created. The wasteland will be fertile once again, and the sun will never set.

It was this image of the messiah that informed the thinking and actions of Jesus. He seems to have designed his teaching experiences to meet the expectations of 2nd Isaiah’s prophecies. And those around him, who thought he was the messiah, knew and understood these apocalyptic connotations.

The common beliefs about the end of the world at the time Jesus began his teachings included several key components. The first sign of the End would the rebellion of Israel, God’s people, against the evil forces of Gog, the evil king of Darkness, identified by all as the Roman Empire. In the hundred years or so prior to Jesus’ birth, several such rebellions had taken place. One, led Judah Maccabee, had almost succeeded. However, every attempt at revolt served only to tighten Rome’s grip.

Following the rebellion would come the Day of the Lord, the Last Judgment, the manifestation of God’s Wrath on the wicked. Then, the nation of Israel would be re-united and all the exiles would return. The dead would be resurrected so that they could experience the final stage, the reign of the Messiah in the new earthly paradise. With, of course, the divinely re-built Temple at the center.

In this context, the role of the Messiah was simple. Defeat the evil King of the World and usher in the golden age. It is difficult to know how Jesus saw himself against these expectations. No one recorded Jesus’ teachings during his lifetime. For 35 years after his death, his ideas lived on only in the spoken words of missionaries and teachers. Jesus’ teachings adapted themselves spontaneously to the expectation of their listeners.

To his contemporaries, Jesus appeared to be a miracle working magi of a sort all too common in troubled Palestine. He is seen by outsiders as similar to other great magicians such Apollonius of Tyana, who also had several Gospel-like Lives written about him. Galilee, Jesus’ homeland, was only recently, a hundred years or so, converted to Judaism and still retained a strong flavor of native paganism. In this background, Jesus’ primary significance derived from his ability to work miracles.

The magi, such as we are told in the Gospel of Matthew followed a Star to Jesus’ birth, were prophet-like figures with distinct ethical and eschatological teachings. Jesus was a similar figure who taught of the Kingdom of Heaven, attracted followers and performed feats of magick. The difference was the specific emphasis on Jewish messianic concepts. Jesus declared himself as the “Son of Man,” 2nd Isaiah’s title for the suffering and triumphant savior.

But the mystery at the core of his teaching was the nature and timing of the arrival of the Kingdom of Heaven. There can be no doubt that Jesus left his early followers with the impression that the world would soon end. His death and resurrection symbolized the triumph of the righteous over the evil King of the World, and His return would herald the beginning of the next phase, the Day of Judgment. He even declared that some living at that moment would still be alive when he returned.

If the end was expected at any moment, then there was no need to record Jesus’ teachings. After many years, when the return still had not happened, the older members of the community began to record their memories. The Gospels came from these early sources. Mark’s Gospel, written around 70 CE, used a common teaching document, known as Q, as the source around which the author wove the story of Jesus’ life. Matthew, the next Gospel to be written down, between 80 and 100 CE, used a similar technique and sources, but applied to them a much greater level of understanding.

Matthew gives us the most complete glimpse of Jesus’ teachings on the End of the World and the coming Kingdom of Heaven. It was written by someone who had grasped the mystery at the core of Christianity. From Matthew we hear of Jesus’ Egyptian connections, the Star of Bethlehem and the journey of the Wise Men from the east, the Massacre of the Innocents, the temptation of the Messiah, and many other stories with deep esoteric significance.

The mystery is openly proclaimed in Matthew at the beginning of Jesus’ career. Matthew quotes the 2nd Isaiah: “the people living in darkness have seen a great light, on those living in the land of the shadow of death a light has dawned.” To fulfill this prophecy, Matthew tells us, Jesus began to preach; “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is near.”

To see this a little more clearly, we need to step outside Christianity for a moment and look at another Egyptian magical text, this one from the Paris Papyrus, one of the gems discovered in Egypt by Napoleon’s savants. In papyrus IV, lines 475-830, we find a ritual to attain immortality through inhaling Light. The aspirants is first told to perform seven days of rituals, and then three days of dark retreat. On the morning of the eleventh day, the aspirant is to face the rising sun and perform an invocation: ” First source of all sources. . .perfect my body. . .(so) that I may participate again in the immortal beginning. . .that I may be reborn in thought. . .and that the holy spirit may breathe in me.”

With this the aspirant inhales the first rays of the rising sun, and then leaves his body behind and rises into the heavens, filled with Light. “For I am the Son (of the Sun), I surpass the limits of my souls, I am (magical symbol for Light).”

In Matthew 5:14, Jesus declares: “You are the light of the world.” This also echoes the Emerald Tablet in equating successful transformation with the spontaneous emission of light or illumination. The Lord’s Prayer, which appears in Matthew 6: 9-13, also suggests the Emerald Tablet. When the Kingdom of Heaven is achieved, Jesus suggests, then heaven and earth, above and below, will be the same. Chapters 24 and 25 provide a blueprint to the coming apocalypse, telling us: “The sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light, the stars will fall from the sky.” He also tells us that it will be “like in the days of Noah” before the return of the Son of Man, except that no one will know the exact day or hour. No one that is except the initiated.

Matthew 24: verse 43 and 44 suggests that those who follow the Son of Man will indeed be able to calculate the time, and so be waiting in preparation. When he returns, chapter 25: verse 31 tells us, he will separate the sheep from the goats, the subtle from the gross, on the basis of their compassion for their fellow men.

In Matthew, we also find the account of Mary Magdalene’s witness to the resurrection, complete with its own light metaphor. “His appearance was like lightning,” we are told, and Mary does not at first recognize him. Matthew’s account of the resurrection ends with Christ’s ascension in Galilee and his pronouncement of the Great Commission. The last line of which goes to the heart of the mystery: “And surely I am with you always, even to the end of the world.”

At the core of Christianity we find an alchemical transformation and the knowledge of the end of time. The Gnostics understood and embraced this view of Christianity. For a brief, shining moment, it seemed as if the knowledge of the path of return was about to triumph over the evil demiurge and his prison of matter. The hope it offered remains the promise at the heart of Jesus’ teachings. As the Gnostics thought, the Messiah opened the way.

And just as quickly, the demiurge closed it again.

More Articles from Sangraal.com:

Submit your review | |